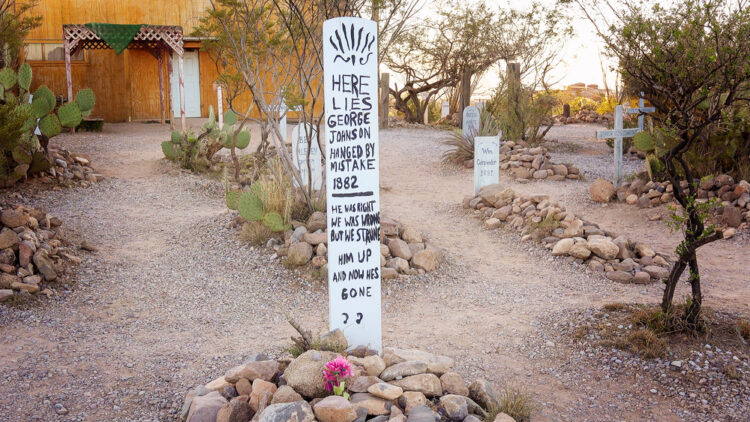

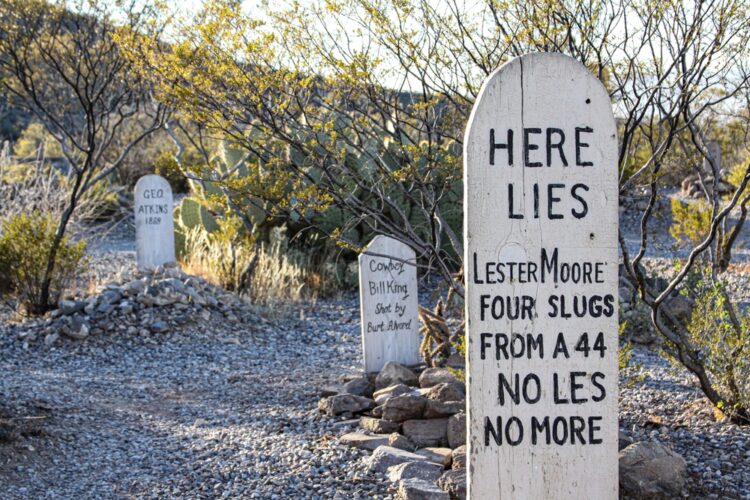

Wyatt Earp still lives, and he is leading a group of visitors through historic Tombstone, Arizona. In the original Boot Hill cemetery, he points out a particular gravestone. The epitaph reads, “Here lies Lester Moore Four slugs from a 44 No Les No more.”

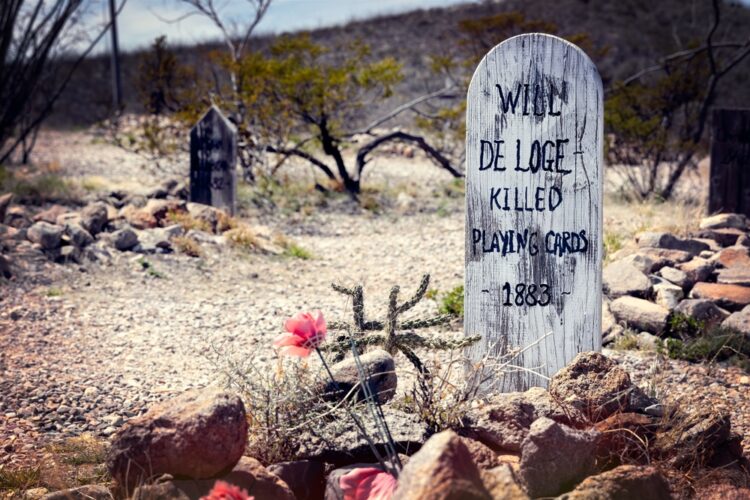

Oft-quoted and credited to gravestone makers throughout the West, this funny epitaph was originally written for the tombstone right in front of us. Another gravestone reads, “Joseph Ziegler Mitered 1882.” Many read, “Unknown.”

In front of each tombstone are masses of rocks. Marshall Earp explains that rocks were a means of keeping animals from digging into the graves, while a fence kept human grave diggers away. Tombstone residents with money paid guards to watch over their loved ones’ final resting places.

A walk through Boot Hill lets us see that old Tombstone was sort of a small, American melting pot, or if not a melting pot, at least an American mosaic. Many Chinese immigrants are buried here. A walk down a small hill leads to a memorial to “The Jewish pioneers and their Indian friends.” In fact, Marshall Earp was married to a Jewish woman from San Francisco, the former Josephine Sarah Marcus.

Earp, played by a local actor Kenn Barrett, accompanies us on a short drive to the historic center of town. As we stroll along wooden sidewalks bordering Allen Street, we pass the Tombstone Photo Studio, where modern day visitors dress in the hottest clothing of the 1880s for souvenir photos. “This is nothing new,” Kenn relates. “These types of photos were actually taken and sold back then.”

Kenn shows us the spot where Campbell and Hatch’s Saloon once stood. Wyatt’s brother, Morgan, was inside playing pool on March 18, 1882 around 10 p.m. when he was shot to death. As we continue walking, Kenn gladly stops for pictures taken by tourists thrilled to encounter Wyatt Earp in the flesh, before escorting us into the Birdcage Theatre. The roughly 140 bullet holes that still pockmark the Birdcage’s interior offer evidence that sometimes things got more than a bit out of hand.

Tombstone, however, is not a reconstructed living history village. It’s a real community. But it is not like a community such as Williamsburg, Virginia, where a modern day city abuts a restored colonial village. Tombstone’s historic district and the places where 21st-century people work and live are one and the same.

The monthly Tombstone Times, a 24-page tabloid, carries advertisements for bed and breakfasts, historic saloons, and shooting galleries as well as real estate agencies, a pet grooming emporium and a town book store, appealing to both those here for a day and those here for 365 days a year.

But real history did happen here, and interpretive markers are posted on and around Allen Street. One noting about the former location of the Maison Doree Restaurant, once advertised as the “finest eating house in the city,” includes a copy of its menu for Thanksgiving Day, 1887. Of course, there was roast turkey and cranberry sauce. There was also a selection of entrees including buffalo tongue and pate financiere.

Another marker in front of a prostitute’s crib– and their rooms were called cribs– describes legal prostitution as “one of the darker sides of

Tombstone’s history.” This darker side isn’t celebrated, but one could say it is exploited. Crazy Annie’s Bordello Bed & Breakfast and Saloon actually was a working bordello. The four guest rooms are named after former “employees”: Soap Suds Sally, Benson Annie, Irish Nellie, and Faro Nell- so as Tombstone Bordello Bed & Breakfast. Big Nose Kate’s Saloon is named for Doc Holliday’s girlfriend, believed to be Tombstone’s first prostitute. Even a Tombstone ice cream emporium is called “Fallen Angel: Sweet Sin Parlor.”

Speaking of sin, let’s go back to the Birdcage Theatre. It was named for the cage styled prostitutes’ cribs suspended from the ceiling, and a row of them still hang there. In 1882 The New York Times reported, “…Bird Cage Theatre is the wildest, wickedest night spot between Basin Street and the Barbary Coast.”

The cages are, however, a small portion of the Birdcage’s ample historic display which makes the theatre interior the closest thing to Tombstone’s attic. The display is cramped, and is low tech and low key; the relics of bygone Tombstone include period photos of entertainers who played at the Birdcage and a tooth extractor strongly resembling a pair of pliers used by Doc Holliday. Most are posted to walls or displayed in glassed-in cases like those one might have seen in their local Woolworth’s a half century ago. In the basement on a dirt floor below the stage is a poker table surrounded by period chairs. One game played on this table was reported to be the longest poker game ever played in the Old West. It lasted eight years, five months, and three days.

That poker game may have been legendary, but it didn’t put Tombstone into the annals of Old West legend, which takes us to the OK Corral, the Ford’s Theater of Tombstone. The 1881 showdown actually took place in an open lot behind the corral. The gunfight is reenacted several daily, frequency depending on the season. It is more Disney than Smithsonian, and the actors encourage the audience to heckle the bad guys. No audience members are brought on stage but the fourth wall is definitely broken. As one of the outlaws approaches the stage, he turns to the audience and bellows, “Are you people ready for a killing?” After a resounding chorus of yeses from the assembled crowd, the actor looks at the audience, pauses, and calls out, “You people are sick.”

Folklore has a way of turning historic figures into heroes. In the gunfight we watch Wyatt Earp, his brothers Morgan and Virgil along with Doc Holliday are the good guys. They order four outlaws (called “cowboys” in their day), brothers Frank and Tom McLaury and brothers Bill and Ike Clanton, to obey a town ordinance by not taking their guns onto the streets of Tombstone. The brothers refuse to turn over their weapons. Words are exchanged, the confrontation exploded and fireworks ensue. When its over, three cowboys are dead and Wyatt’s brothers and Holliday are seriously wounded.

Not so fast, says Tombstone historian and writer Joyce Aros. In her 2013 book, Murdered on the Streets of Tombstone, Aros uses archived contemporary interviews and legal papers to conclude that the Earps were hardly good guys. They were the aggressors, and Wyatt was trying to raise his profile as a no-nonsense lawman because he planned to run for county sheriff.

However, Kenn Barrett points out that Judge Wells Spicer stated in the case against the Earps, “I cannot resist the conclusion that the defendants (the Earps and Doc Holliday) were fully justified in committing these homicides– that it was a necessary act, done in the discharge of an official duty.

You can watch the gunfight when you visit and decide for yourself.