It seems unlikely that anything could be thrilling enough to waylay me when I’m walking to Victoria Falls, already armed with a rain coat and a silly grin.

But when the hotel gardener I’m breezing past says: “Hello, do you want to see the giraffes?” it stops me in my tracks.

I’ve never had an offer like that before, so I instantly say yes and follow him into the scrubby bushes.

I’d already seen zebra grazing outside my bedroom and spotted three giraffe in the glorious grounds of the Royal Livingstone Hotel on the Zambian bank of the Zambezi River.

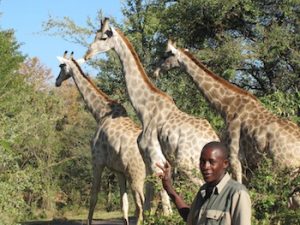

Gardener Kennedy Muzala knows their favourite hangout, and leads me there while making a knocking, rattling guttural call to let them know he’s coming. It sounds like a death rattle, but it does the trick. The giraffe stand perfectly still like cutout models against the bright sky as we step ever nearer.

I draw so close to one that we’re looking into each other’s eyes. She’s looking down, obviously, because I’m only as tall as her elegant legs. It’s an awe-inspiring privilege, and I quietly thank her for letting me come so close.

It seems unlikely that anything could be thrilling enough to waylay me for a second time when I’m walking to Victoria Falls, now sporting an even sillier grin. But as I head towards the largest waterfalls in the world I spot Edward Minyoi, and plans go awry again.

It’s hard to miss him in his multi-colored kilt and waistcoat, black bowtie and bright red beret. Minyoi is the resident storyteller, speaking enough words in a rainbow of languages to make international guests feel welcome.

He’s a member of the Lozi tribe from the west of Zambia, and his outfit is called a Csiziba. When the river floods and water spills over the plains, the tribesmen don their Csiziba and row their chief from his palace up to dry higher ground. That must be a fine sight, men in kilts paddling a canoe across African floodplains. “We got this cultural style from the Scottish in the 18th century,” he says.

We sit on the lawn that leads down to the Zambezi, watching the plume of spray that rises up from the Falls and changes the sky from blue to white. I ask him to tell me a story, in English, please, not in Russian, German, Spanish, Italian, Greek, Zulu, Japanese Chinese or Cockney Rhyming Slang.

I’m enthralled as he tells a vivid tale of a man who was fishing from a boat when a crocodile attacked. As he tumbled into the river his legs sank deep into the mud. The croc gripped him in its jaws but couldn’t wrestle him free from the mud before other fishermen beat the croc away. It took five hours to reach the nearest hospital by ox wagon, where the man spent seven months recovering. “Phew,” I say appreciatively, thinking Minyoi has finished his story, but he’s just taking a dramatic pause. “When he came home he asked his friends where the fish were that he’d caught before he was attacked. The men said they’d sold them, and gave him the money they’d saved for him.”

Finally I’m back on the path to Victoria Falls, and nothing can waylay me now, not even a baboon that lashes out and scratches my leg when I walk too close. I back off and take a different path, now brandishing a branch as a monkey-repelling stick.

The first view of the Falls is gorgeous – a thunderous torrent of water artistically framed by trees dripping with its spray. At other viewpoints I can hear millions of liters of water crashing down just a few meters away, but I literally can’t see them for the spray that’s raining down on me. I’m laughing with the exhilaration of being absolutely drenched by the biggest waterworks on the planet.

I was last here in dry season, when the Falls on the Zambian side were practically dry. I can see the point where my guide and I ducked under a fence and stood on the rocks at the top. Now the river is sweeping over those rocks, meandering slowly until it suddenly plunges into the abyss. The wind shifts, the air clears, and the Falls are suddenly visible again, a vast unstoppable curtain, with double rainbows shimmering perfectly to one side.

I cross to the Zimbabwean side the next day for viewpoints of almost the full 1.7km width, where you’re observing the Falls rather than feeling a part of them. Once you’ve experienced Victoria Falls from both Zambia and Zimbabwe, which share this stunning treasure, you have to see them from above. The doof-doof-doof of helicopters has become a background irritation that detracts from the natural atmosphere of the Falls, but it’s an annoyance I conveniently forgive as soon as it’s my turn to fly.

The good-looking pilot invites the good-looking girl to sit in front, while we three others frump our way into the back. The views are absolutely stunning. And it’s easy to spend all your time trying to get good photos instead of really looking at the view and creating incredible memories. I put away my camera and just admire the spectacle. So much water, such an unstoppable force of nature.

When you visit Victoria Falls it’s brilliant to stay within walking distance, in a hotel where your room key gets you free entrance to the viewpoints. The Royal Livingstone and its more modest sister hotel, the Avani Victoria Falls Resort, sprawl beside the Zambezi River in Zambia, and it’s incredible to roll out of bed, pull on some clothes and stroll to one of the most spectacular sights on earth.

Both hotels have spas offering treatments in gazebos by the river and share a cultural village with a few of traditional huts. Villager Maggie Sambo explains the medicinal uses of barks, seeds and leaves, then picks up an insect nest the size of a tennis ball. The nest is boiled to make a medicine to cure high blood pressure, she says, and my pulse races at the very idea.

Other attractions in the areas are game drives in Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park, zip-lining through the gorges below the Falls and bungee jumping off Victoria Falls Bridge. Far more sedate is the charming Royal Livingstone Express, a dinner train that parks near the bridge while you eat delicious food in eclectic company. My companion swore that the young couple on next table were British royalty travelling incognito, as we eavesdropped on their terribly upper-crust accents.

It seems unlikely that anything could be thrilling enough to waylay me when I’m dripping my way back from Victoria Falls in dire need of a towel and dry clothes. But it’s high tea time at the Royal Livingstone, with beautifully laden cake-stands dislayed like they have been since explorer Dr Livingstone first brought British eccentricities to the heart to Africa.

I help myself to a dainty lemon meringue pie, knowing everyone is far too polite to comment on the puddle of water I’m creating on the terrace.

For details of the hotels see