There they are, on full display in front of you: George Washington’s legendary false teeth, looking more like Johnny Rotten’s. The uppers aren’t that worse for wear, but the lowers have gaps that one could drive a truck through. But they are not made of wood as many believe. The first president’s choppers were crafted from the combination of elephant ivory, human teeth, and cow teeth.

Despite the shoddy state of the stained dentures, Washington actually practiced pretty good dental hygiene. He brushed daily but suffered from repeated dental problems. While he was leading the rebellion against the Crown, his teeth were rebelling against him, resulting in abscesses and other dental maladies that caused him to rely on a mouthful of fake teeth by the time he was 57.

Those who last visited Mount Vernon in the dark ages of the 20th century might be surprised to see how much has been added. The mansion is still the main lure, but it is almost supplementary to the other sites here. We learned Washington’s dental information while inside the fairly new– opened a decade ago –Donald W. Reynolds Museum and Education Center, a fairly dull name for a lively museum. It is similar to a modern day presidential library/museum with life-sized dioramas (Washington the surveyor, Washington the general on horseback, Washington taking the Presidential Oath of Office in New York City) and a half dozen videos exploring George Washington far beyond battles and presidential policies.

One can take a seat inside a reproduction box church pew like the one from Pohick Church in nearby Lorton, Virginia where the Washingtons worshiped, and hear the general’s prescient views regarding religious freedom. Included in his iconic letter to the congregation of Newport, R.I.’s Touro Synagogue, which contains the famous sentence, “It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoy the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.”

Another video tells the tale of George and Martha’s life-long romance, regaling us with stories of young George Washington’s courtship of the wealthiest widow in Virginia and the strength that made their marriage last for 40 years. One more delves into espionage 18th century style, with stories of invisible ink, the hiding of letters in the buttons of children’s jackets and something as simple as a woman hanging a dark cape on a clothesline to alert the allies that a message was there.

In the same building is the museum portion of the Reynolds complex. It is evocative of a fine arts museum rather than a modern-day presidential library. Mount Vernon’s most prized artifact is the bust of the first president, sculpted out of clay in 1785, and is the first thing one sees inside. Personnel here say it is the most accurate likeness of Washington ever created.

The museum galleries are arranged by topic such as home life, military life, and personal style, the latter home to Washington’s shoe and knee buckles and Martha’s earrings and necklaces. It turns out the first lady was pretty handy; inside one display case is one of twelve shell-patterned canvas work chair cushions she stitched. In the military gallery is Washington’s bedstead, dating from around 1775; the general used it while on the field of battle.

There are also a couple of original oil portraits of Washington by Charles Wilson Peale. One of Washington after the Battle of Trenton features the the general in full military regalia, and it makes an observer wonder how anyone could fight a battle donning such fancy duds. The most splendid exhibit might be the elegant dining room table, set up to represent the meals Washington hosted for government officials every Thursday at 4 p.m. at the presidential residence in Philadelphia. Several pieces, including the French porcelain dinner service and table ornaments, finger bowls and silver candlesticks are Washington family originals.

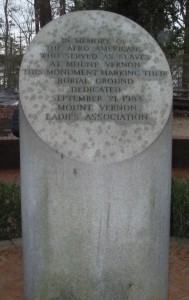

When I first visited Mount Vernon in my childhood there was little mention about slavery; since then this has been fully addressed. A memorial to Washington’s slaves and their dependents was placed over a Mount Vernon slave burial ground in 1983, and a nearby marker explains that when Washington died in 1799 there were 318 slaves working on the property. Most did agricultural work but about 25 percent were skilled crafters.

Walk through the numerous outbuildings and you will see where slaves lived and worked. The barrack-style men’s and women’s greenhouse quarters where slave craftsmen resided are replicas constructed in 2010. The buildings are sturdy and constructed of brick, as are the floors. (On the other hand, most slaves who worked on farmland spent their nights in fairly shoddy cabins.) In order to sleep comfortably, slaves covered the wooden bunks with straw. Other outbuildings include the spinning room, the blacksmith shop and the smokehouse. The Washingtons were known for having some of the best Virginia smoked hams around and Martha proudly gave them as gifts to her friends. Replicas hang from the smokehouse rafters.

And yes, there is also the mansion. Here George and Martha lived, ate, and slept. Mount Vernon, not Elvis Presely’s Graceland as often reported, is the most visited private home museum in the country with a little over one million paying visitors a year.

Before entering the mansion, go ahead and touch it. What looks like cut-stone blocks sure doesn’t feel like them. Thanks to a process called rustication, wood planks were beveled, painted, and sanded to look like stone which was much more expensive than the pedestrian wood. This was an early American way of keeping up with the Joneses as well as the Jeffersons and Madisons. If the house looked expensive, people would think it was expensive.

A total of 14 of the mansion’s 21 rooms are open to the public, yet the house may have seemed like it was open to the public when the Washingtons lived there. The two were avid entertainers, much of the time the mansion’s ten bedrooms were occupied by friends.

Staff member Melissa Wood says that the New Room is overwhelmingly today’s visitors’ favorite chamber. In Europe the New Room would have been called a salon. People like it not only for its size but for decor and historical context. It was here that the Washington’s hosted parties and receptions for the day’s VIPs. It is also possible that Washington was in this room he heard that he was unanimously elected president of the United States.

The New Room is saturated in vivid green wallpaper (the use of bold colors was a sign of wealth), and tall, airy windows. A half dozen oil landscape hang on the walls, evoking all-American settings including a fanciful view of the Hudson River Valley and a more literal depiction of the rambling Potomac River. Before exiting, look up. How many plants and farming tools can you recognize in the ceiling’s carvings?

A little less than three miles from the mansion is Washington’s reproduced distillery, opened to the public in 2007. Washington’s specialty was rye whisky and shortly before his death he was one of the largest producers of whisky in the country.

George Washington: surveyor, general, statesman, president, distiller? Who knew?

If you go:

Mount Vernon is open 365 days a year.

Hours are: 9am- 4pm November through March, 9am- 5pm the rest of the year.The distillery and nearby gristmill are open April through October, daily, 10am- 5pm.

Admission: $17 ages 12-61; $16 ages 62 and over; $9 ages 6-11. An audio tour handset can be rented at $7 per person; $6 if ordered online.

Plan to spend a minimum of three hours here, a few hours more if you’re the kind of person who likes to see everything.

Information: www.mountvernon.org; tickets@mountvernon.org; (703) 780 2000.