A lot has happened since the pictures of devastation from the usually quiet municipality of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, USA made headlines 20 years ago. Heart-wrenching images of a bombed office building and broken bodies, the kind we are used to seeing from the Middle East and not the American Midwest, were on television screens and in newspapers in parts of the world that never knew Oklahoma City existed. The date was April 19, 1995. The time was 9:02 a.m. The Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, in the middle of downtown in the Oklahoma state capital, exploded with a hellish boom that people could hear 30 miles way. “Like a sonic boom, except at least 100 times louder,” said survivor Cathy Jean Coulter.

Right away first responders knew the cost in humanity and lives was devastating. Two militant anti-government Americans and former Army buddies, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols, were captured shortly afterwards, and in time, tried and convicted. McVeigh was put to death. Nichols is serving life in prison.

© Michael Schuman

© Michael Schuman

But in those 20 years, the faces of both the nation and world have changed. According to Kari Watkins, Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum Executive Director, over 51% of the current people currently residing in Oklahoma City were either not living there or were not alive in April 1995. To reach the new audience, the museum foundation unveiled earlier this year a $10 million dollar renovation. Previously, the majority of museum exhibits focused on the spirit of altruism and community that has become known as the Oklahoma Standard. Galleries were titled, “Inner Strength, Outer Resolve,” “Healing of the City,” and “`We Will Be Back’ – A City rebuilt.” They remain today.

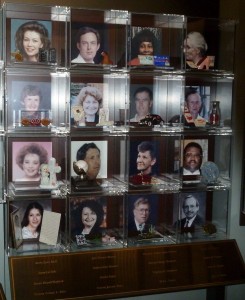

Similarly, the 168 fatalities played a major role in the museum experience. The Gallery of Honor, a memorial rotunda with photos and personal artifacts of most of victims who went to work that day and never returned home, is still there. Family members were asked to submit a telling item from their loved ones’ lives to be placed in a shadow box by their photo. There are angels and Bibles. There are identification cards; Murrah employee and part-time fitness instructor Karen Carr is represented by her business card reading, “Fit Feds.” There are a stethoscope, a charm bracelet, a Barney soap dish and a child’s palette and paint brush.

© Michael Schuman

Deborah Gomez, said of her mother Margaret Goodson who died in the bombing, “I didn’t put anything in her box at the memorial… I wanted the empty box to represent the emptiness in our lives because my mother is no longer with us.” Boxes of tissues are supplied just outside the Gallery of Honor to dry anticipated tears from visitors.

© Michael Schuman

The museum may not be a fun place to visit, but it warms the heart with stories of courage and hope, that maybe Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols are the exceptions, not the rules, that the majority of humanity consists of people like the firefighters and police officers who risked their lives in the rescue efforts, and the innumerable volunteers who continued to bring life-saving supplies even after no more were needed.

While the attention to both the Oklahoma Standard and the victims has remained, the renovation brought more coverage of the actual crime. Watkins says, “It was time to update the museum and keep it relevant to a new generation who doesn’t know the story. When the museum first opened in 2001, the justice part of the story was still ongoing and the legal teams and investigative artifacts weren’t available to us. Visitors frequently asked for more information about that important chapter of the story.”

© Michael Schuman

The car McVeigh was driving when he was pulled over by State Trooper Charlie Hanger about 90 minutes after the bombing is now parked in front of a tableau of the Interstate 35 section where McVeigh was arrested. Many who recall the bombing don’t remember that McVeigh was pulled over for a routine traffic stop. He was taken into custody for having a concealed handgun. At the time Hanger had no idea McVeigh had any connection with the bombing.

A new wall-sized electric map titled Trail of Evidence highlights the places across the country where the investigation led. The Responsibility Theater asks the audience questions relating to liberty, judgment and courage. Example: would you alert authorities if one of your best friends seemed to planning a crime? It was discovered that McVeigh’s close friends Michael and Lori Fortier were fully aware of McVeigh’s plan to bomb the Murrah building and did not report it. Lori turned state’s evidence and testified against McVeigh.

Of course, much hasn’t changed. The first galleries recall the bombing’s immediate aftermath: confusion, chaos, and the realization that the ear-busting burst of sound was not a tornado or a boiler explosion. Glass from the Murrah Building fell for ten minutes like rain in an Oklahoma thunderstorm. Some survivors still carry shards of glass in their bodies. The black and white clock stuck at 9:02 rests amid a broken folding chair, metal slats and other rubble. Key chains, single shoes, a crumpled calendar and a smashed telephone represent victims. U.S. Department of Transportation employee Rick Tomlin was on the phone with his wife Tina when the bomb hit. The line went dead. She never heard his voice again.

© Michael Schuman

Outdoors, a reflecting pool occupies what was once N.W. Fifth Street, which bordered the Murrah Building’s front entrance. The 168 fatalities are remembered outdoors in a field of empty chairs, known collectively as the Outdoor Symbolic Memorial. The glass base of each chair is marked with a victim’s name. Clint Seidl, seven years old at the time his mother died, said “It would make me proud if someone got tired and they could maybe sit in my mom’s chair. I’d probably walk up and say, `Hi. I’m Clint Seidl. This is my mom’s chair.’”

There is also one singular survivor that has taken on special meaning. A 90-year-old American elm growing in a parking lot across from the Murrah Building withstood the blast, but not without inhaling pieces of shrapnel and glass. Every year the facilities and grounds crews collect seeds from the tree and grow them into saplings, which are then given to family members of those killed. The elm became known as the Survivor Tree, emblematizing the spirit and resilience of Oklahomans.

IF YOU GO

Hours: The Outdoor Symbolic Memorial is open year round, daily, 24 hours. National Park Service rangers are on the site daily 9-5 except for Easter, Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. The museum is open daily (Monday-Saturday, 9-6; Sunday, 12-6) except for Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. The last museum ticket is sold at 5 p.m.

Admission: free for the Outdoor Symbolic Memorial; $15 adults, $12 for ages 62 up, military with ID and ages 6-17 or college student with ID for the museum.

Information: (800) 542-4673, (405) 235-3313

www.oklahomacitynationalmemorial.org

Oklahoma City lodging: Hampton Inn — Bricktown, 300 East Sheridan, (405) 232-3600, www.oklahomacitybricktownsuites.hamptoninn.com Sleep Inn, 4620 Enterprise Way, (405) 946-1600, www.sleepinn.com Colcord Hotel (boutique hotel, first skyscraper in city, dates to 1910), (405) 601-4300), 15 North Robinson Avenue, www.colcordhotel.com

-0-