The Mississippi River. The blues and jazz and paddle wheelers, poker-faced riverboat gamblers, Tom Sawyer and the Big Mo, and music meccas New Orleans, Memphis and St. Louis.

Not here. Not in Minnesota, especially north-central Minnesota. The mighty Mississippi isn’t so mighty in the Land of 10,000 Lakes. Up north, it’s pretty humble.

One can walk across the Headwaters of the Mississippi, where Lake Itasca morphs into the nascent river. It’s not exactly a trickle at its source, as some may have heard. But it is hardly the big, fat, muddy behemoth most of us are so familiar with. It’s about the size of your basic state park brook, alongside which one might unfold a tent and settle in for a night of cooking hot dogs and roasting marshmallows. And it is ankle deep. One can easily walk from one bank of the river to the other, stepping across its rocky bottom. Another option is crossing the river on the bridge of rocks that spans its beginning.

Itasca is not an American Indian word (The Minnesota Indian Affairs Council prefers the term “American Indian” over “Native American”). The lake was named by explorer Henry Rowe Schoolcraft as a combination of two Latin words: veritas, meaning “truth,” and caput, or “head.” It’s appropriately located in Itasca State Park, though astonishingly the park, founded in 1891, was not initially established to preserve the great river’s source. Its initial raison d’etre was protection of Minnesota’s three native pine trees (white, red and jack) from cash-hungry lumber companies, and today the red pine stand in Preacher’s Grove is a pleasant if not overwhelming place to get out of the car and stretch one’s legs.

Two visitor centers and a scattering of interpretive markers throughout the park offer insight to this special place. The first Europeans to discover the Mississippi’s source were those on an expedition led by Schoolcraft and guided by an Ojibwe Indian named Ozawindib. The year was 1832. Today, the park draws about 500,000 visitors a year.

Those not planning on prepping for an appearance on Jeopardy might be more inclined to read the human interest stories posted in the Jacob V. Brower Visitor Center. There is an emphasis on Civilian Conservation Corps employees who worked here during the Great Depression. And there are some insightful pull quotes from correspondence sent home by vacationers in years past. One prairie resident marveled at the mere sight of trees, writing on August 14, 1924, “For one who sees nothing but cornfields, the pines are a wonderful treat.”

Another vacationer scribbled on the back of a postcard in 1937, “The mosquitos (sic), my wife and I had a most enjoyable time.” Perhaps his descendants, like those of the mosquitoes, are here. Bug spray is a necessity if one plans to venture

into the woods.

It’s virtually impossible to explore this region without encountering the presence of Native American culture. Outside the Mary Gibbs Mississippi Headwaters Center is a curious bronze sculpture of an Ojibwe woman, hair flowing like the waters of the river, and holding a basket of baby turtles. To the Ojibwe people, turtles are symbols of both water and the cycles of life.

The river toddles in northern Minnesota but by the time it reaches the Twin Cities, it sprints. A total of 72 miles of the river in this urban locale is now part of the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area, basically amounting to be a conglomeration of river-related historic sites and recreational opportunities. Its purpose is to preserve the role of the Mississippi in shaping the nation’s character.

There is only one major waterfall on the entire 2,552-mile-length of the Mississippi. St. Anthony Falls was captured and exploited by for its waterpower by early settlers and entrepreneurs, including a New Hampshire expatriate and miller named Charles A. Pillsbury. In time, Pillsbury’s pet project grew into the largest flour mill in the world.

The stark and stony ruins of a competing mill form the nucleus of the Mill City Museum, where multi-media presentations and other exhibits place the heritage of the mills, its owners, its products, and its workers under a microscope. The museum sits under the watchful eye of a Gold Medal Flour sign, standing like a silent sentinel atop the old mill complex. Inside are hands-on baking and water labs and a multi-media presentation in which the audience stands in an old service elevator and watches as stories of Pillsbury past are regaled on screen when the elevator stops at different floors.

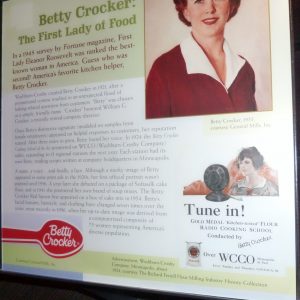

According to a displayed poster, this is the “The Cradle of Carbohydrates.” Further exhibits inform visitors on everything they might ever want to know about the history of Betty Crocker, Bisquick and Wheaties. There never was a real Betty Crocker, but in 1945 a Fortune magazine survey revealed that she was the second most recognized American woman after Eleanor Roosevelt.

Speaking of presidential ties, one reads that a radio broadcaster in Iowa once won a contest for broadcasters whose shows were sponsored by Wheaties. His prize was a trip to Hollywood. His name? Ronald Reagan.

Specialized walking tours along the Mississippi’s banks are an additional museum feature. We took one on disasters of the Mississippi and we heard more about explosions, fires and floods. The most horrendous disaster occurred on May 2, 1879. The culprit was rapid combustion of flour dust and every person engaged in the mill at the time instantly died. Prefer a more benign topic? Other tours cover everything from nineteenth century working conditions to the engineering knowhow that made the mills work to the influence of the railroad on the mills.

The river’s first junction with a major tributary is in St. Paul, but the Mississippi’s confluence with the Minnesota River doesn’t necessarily transform the Mississippi into the old man it is a few hundred miles south; here, it’s more of a young buck. To the Dakota people, this confluence had deep, spiritual meaning; it was the setting of the birth of civilization, their Garden of Eden. To European settlers, it was a center of trade and military activity.

The confluence today is part of Fort Snelling State Park (as opposed to Historic Fort Snelling nearby). A five-minute walk along the paved and gravel path leads to the spot where the rivers meet. Surprisingly, there is no historic marker, only a pole indicating the crest of past floods. Standing here, one might think the surrounding city of St. Paul is a million light years away. Egrets fording the sometimes mossy waters and turtles resting atop rocks add to the illusion.

Oh, and the genesis of the name “Mississippi”? Some say is has its roots in a Chippewa word meaning “father of rivers.” Another theory is that it is a corruption of the French word, “messipi,” or “great river.” No other names would be appropriate.

IF YOU GO

The best place to begin your visit at Itasca State Park is the Jacob V. Brower Visitor Center near the park’s East Entrance. Additional information can be found at the Mary Gibbs Mississippi Headwaters Center.

- Admission: $5 day vehicle permit, $25 annual vehicle permit good at all Minnesota state parks.

- Hours: park open 8 a.m. to 10 p.m.; Jacob V. Brower Visitor Center: 8-8 in summer, 8:30-4 rest of year.

- Mary Gibbs Mississippi Headwaters Center: outdoor exhibits open 8 a.m. to 10 p.m.; gift shop open Memorial Day-mid-October, 10-5.

- General park information: (218) 699-7251 (best to call between 8:30 to 6 in summer and between 9 and 3:30 in winter).

The best place to start your exploration of the river’s urban setting is the Mississippi River Visitor Center, located at the Science Museum of Minnesota, 120 West Kellogg Boulevard, St. Paul, (651) 293-0200. There you can learn information about everything from guided kayaking trips to flora and fauna.

- Hours: Year round, Sunday, Tuesday-Friday, 9:30-5; Friday and Saturday, 9:30-9. The visitor center has a moderately-sized exhibit area and admission is free.

Mill City Museum, 704 South 2nd Street, Minneapolis.

- Hours: Tuesday – Saturday, 10-5; Sunday, 12-5; Mondays in July and August, 10-5. Admission: $11 adults, $9 ages 65 and up and students and active military with ID; $6 ages 6-17, (612) 341-7555.

Fort Snelling State Park, 101 Snelling Park Road, St. Paul.

- Hours: Year-round, visitor center 8-4, park 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. Admission: $5 day vehicle permit, $25 annual day vehicle permit good at all Minnesota state parks. (612) 279-3550 (0ffice), (612) 725-2724 (visitor center).

- Lodging: There is no camping at Fort Snelling State Park. Itasca State Park has drive-in, electric, RV-length, wheelchair accessible and backpack campgrounds. Prices range from $12- $23. For reservations, (866) 857-2757 or book online.

Douglas Lodge in Itasca State Park is a log-constructed building dating from 1905. A variety of rooms ranges from $75 to $138, with highest rates in summer. Roughly a couple dozen cabins are also available, nights ranging from $105-$215. There are 12 Itasca Suites with modern facilities, off-season $99, summer $138.

- Reservations: (866) 857-2757, phone center open 8-6 Monday-Friday, 8-2 weekends from October to March and 8-8 daily April through September.

Motel: C’Mon Inn, 1009 1st Street, E., Park, (218) 732-1471, doubles: $99-$145, breakfast bar included.

Twin Cities lodging:

- The Commons Hotel, 615 Washington Avenue, SE, Minneapolis, (612) 379-8888, doubles: $199-$299.

- Doubletree by Hilton St. Paul Downtown, 411 Minnesota Street, St. Paul, (651) 291-8800, doubles: $109-$219.