Spaniards may take a relaxed mañana attitude to things like completing half-built cathedrals and scoring World Cup goals.

But when they say that access to a train closes two minutes before the departure time, they actually mean it.

“The train has gone,” a square-shaped security guard told me with an indifferent shrug.

“Not it hasn’t,” I panted, “I can see it.” I pointed it out, large and definitely present, as a loud speaker tauntingly confirmed that the train for Toledo was boarding at platform seven.

But a large Perspex shield was blocking the entrance to the platform. “It’s gone,” the guard repeated, no doubt slyly enjoying the sight of the Spanish train system defeating yet more tourists.

We’d had plenty of time for our planned day trip to Toledo, a towering medieval city just a 35-minute high-speed train ride south from Madrid. But we had to figure out perplexing options on the ticket machine, run up and down in search of a platform as cunningly located as the platform to Hogwarts, then pass our bags through the security scanner only to rush nose-first into the Perspex screen. We sheepishly retreated to the customer service center, where a helpful assistant sold us an upgrade to the next train.

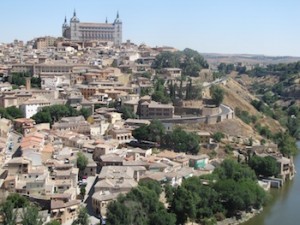

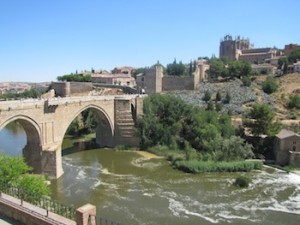

Toledo is an ancient and spectacular city that encompasses most of Spanish history into one compact example. It stands on a hill with expansive views over the surrounding land so the locals can see who is coming to invade them next. And come they did. Evidence of early settlers begins in the Bronze Age, long before successive waves of aggressors that included the Romans, Moors, Visigoths, and Vandals. And now the tourists, besieging Toledo on a daily basis to disrupt its peace, plunder its bars, restaurants and gift shops, and lay siege to its amazing monuments.

Toledo was the Spanish capital until the court was moved to Madrid in the 1560s. It’s a remarkable city, with a tangle of cobbled streets twisting between the massive walls of one spectacular building after another.

Arriving at the train station requires a brisk 20-minute march up the hill to enter through the sturdy walls. We took the easy option of the open-topped tourist bus, which runs in time to meet the crowded trains arriving from Madrid and Barcelona.

At €9 a ticket, it’s quite pricy since a double-decker bus can’t show you much of the city because the streets are so narrow. However, it is useful for reaching a panoramic viewpoint to see the whole city laid out magnificently across the River Tagus.

Then the bus drives past a couple of hotels on the outskirts, gradually sneaking up on the center like a Trojan Horse bearing the newest generation of marauders. The skilled driver performs a five-point-turn to negotiate some tighter corners, collecting anxious looks from car drivers not expecting to meet our tourist chariot in a street designed for horses.

The bus delivers you to the peak of the hill beside the mighty Alcázar, first built as a Roman fort then later extended into a palace by King Carlos V. It has a brutal history of treason, murder and sieges, with the last siege staged as recently as 1936.

It’s now an Army Museum where you finally begin to understand just how many nations have fought over this prime piece of land. Shining ranks of armor standing behind glass frames still look unnervingly ready to shatter the windows and lay waste to the gawping tourists.

The city also has a macabre museum displaying instruments of torture perfected by the Spanish Inquisition, when religious zealots persecuted, converted, or killed anyone not conforming to their own increasingly narrow definition of what constitutes a good Catholic. We passed that one by for the altogether jollier prospect of lunch in the sun in a narrow cobbled alley I’d never be able to find again.

We drank red wine and beer and ordered chilled gazpacho soup and chicken strips. The gazpacho came in a bottle that I mistook for tomato sauce. It was only when I told the waitress that I was still waiting for my soup that she pointed out the bottle, now warming up nicely in the Toledo sun.

Although the sun was fierce, the breezy higher altitude keeps it cooler than the capital, so it’s a hugely popular place for tourists and day trippers, including local Madrileños.

It’s only when you arrive that you realize how much there is to see to really do Toledo justice. From the twin towers of the Baroque Jesuit Church, dating from 1742, you look down on a jumble of terracotta roof tiles. Most of them are covering ancient monuments of one sort or another, often in that sturdy Gothic style designed to intimidate rather than enchant. Even the cathedral is a squat and solid fortress-like affair, dating back to 1226 but only finished in 1493 in yet another fine example of mañana.

My camera was working overtime at the succession of glorious buildings. It’s a maze of a place, and we’d set off in one direction confidently holding the map, only to emerge a while later at a point behind where we first started. We made it to the El Greco Museum, hoping to see the paintings of El Greco, the nickname for the expressionistic artist Doménikos Theotokópoulos. He died in Toledo in 1614 so the city is abuzz with 200-year anniversary celebrations. The museum itself was abuzz with two large tour groups who descended a minute before we did, so we backtracked down another alley to get lost again.

It must be entrancing to roam the streets once the last tourist bus and the final train have departed. Then you’d really feel the imposing stillness of the formidable walls, the ghosts of centuries of raiders and defenders. You could get lost and lonely in the winding streets, not swept along by clusters of sightseers led by guides speaking into lapel microphones.

I popped into the grand-looking Hotel Alfonso in the attractively named Cuesta De Capuchinos road to check the room rate. It’s in the center of the city and I expected it to be substantially higher than we were paying in Madrid. Wrong; it was 30% cheaper and 100% more historic.

But the tour bus was waiting to take us back to the train station, where a long queue snaked right back to the entrance to the ornate building. There were fifteen minutes to go and at least 200 people that needed to be scanned and boarded. As we pulled away, the empty seats on a supposedly fully-booked train meant a few stressed tourists were watching us leave from behind the Perspex barrier.