My French came back to me with remarkable clarity as I staggered out of the ocean clutching my stinging ankle.

“Je suis blessé,” I wailed, then proved I was injured by tumbling over as my ungainly flippers snagged on the volcanic rocks peppering the beach. Something that felt suspiciously like a crown of thorns had gripped my ankle as I’d waded through the murky water. Now my ankle was punctured by five black splinters and dark, angry patches were swelling around them.

You can’t move with speed or grace in flippers on dry land, so by the time I reached the hotel several onlookers were watching with amusement. Philippe the manager inspected my ankle and frowned. Sea urchin spines, he said, and there’s no way to remove them.

Telling a city girl she’s been permanently impaled by a sea urchin is akin to telling her she’s caught bubonic plague, which also seemed possible since I was in Madagascar, where the medieval disease recently resurfaced.

If you’ve seen the movie Madagascar and imagine an island filled with adorable little critters, forget it. The real wildlife is a lot less friendly. I’d quickly accrued a collection of 78 bites from various assorted insects, which show an alarming disrespect for liberal lashings of repellent. Now I’d stumbled over a sea urchin, and I gulped as Philippe explained that the calcium spikes break up if you try to remove them. So they must be pushed further in then dissolved with acidic papaya juice so my body could absorb them.

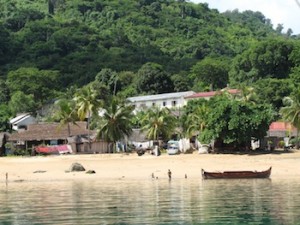

I wobbled over to Gilbert, the boat captain at Anjiamarango Beach Resort on Nosy Bé, a tiny island off the northern tip of Madagascar, an enormous island off the east coast of Africa. Gilbert produced the sort of knife that could steal your life in a darkened alley. It had clearly been used for stirring paint too, but in Madagascar everything serves multiple purposes if the proper utensils are in short supply.

He scraped the wounds, then thankfully turned the knife around and used the handle to bash down on the spines. Then he pierced a papaya skin and smeared its acidic juice onto each wound.

By now some good-looking Frenchmen in très petit swimming trunks had gathered, so I swooned a little and asked if I was going to die. Non, they reassured me, you’ll survive. And have really strong bones thanks to the extra calcium, we joked.

Madagascar’s cutest animals by far are the lemurs, those big-eyed, fuzzy-haired primates with tails as long as feather boas. One morning we took a taxi from our hotel to a small town and caught a speedboat to the island of Nosy Komba, a lemur sanctuary. Our guide Axel walked us through a little village of wood and palm-leaf houses with a couple of sturdier brick buildings in between. One was the hospital, a grubby, shabby shack that steeled my resolve not to have any more close encounters with dangerous wildlife.

At the start of a slippery forest trail we were joined by another guide, cunningly armed with bananas. Soon he began calling ‘monkeymonkeymonkeeee’ and pointed to some rustling branches. Big eyes under a bad-boy haircut broke through the leaves. My first lemur sighting! Our guide plopped some mushed up banana on my hand and the lemur swung onto my arm, using a delicately hand to grab the fruit. He seemed to like me, and crawled around my shoulders then perched on my head like a furry turban.

We made it to the top of the hill, where the guide laconically pointed out the view and started down again. At the bottom we browsed in a tiny craft market before Axel led us to a beach bar where the ocean was bathwater warm. We ate a simple but delicious meal of skewered prawns, fried fish and salad, followed by the sweetest pineapple and mango.

Madagascar is a former French colony, so French is the official language but the atmosphere is distinctly African. It’s a lazy holiday destination, with the traditional sun, sea and sand combination made more interesting by the sheer volume of wildlife to be explored. You can visit turtle reserves, the lemur islands or go diving, snorkeling, quad biking or just walk through villages where the locals eke out a meager living off the land.

It’s also one of the poorest countries in the world, according to the United Nations’ measurement of life expectancy, education and income. The average Malagasy earns around $1 a day, but the economy could improve if the peaceful elections last December restore political stability and international aid returns. The poverty has also spawned a makeshift ingenuity. A quad bike tour of Nosy Bé took us through tiny clusters of palm-leaf houses, with chicken and goats roaming outside and women pounding grain with enormous pestles.

We drove onto beaches to explore mangrove swamps and our guides showed us wild vanilla and ylang-ylang trees used by perfume houses, and a haughty chameleon that made every step a dance move shuffle. At one stage a quad bike broke down, just as a young boy driving an ox-cart appeared out of the forest. He jumped off, eager to help our guides as they bashed and beat the offending wheel back into action.

The Anjiamarango Hotel is a sturdy but pretty place built from the local materials, with a restaurant, an airy upstairs bar and a large, beautifully warm swimming pool. A late night dip beneath a million stars is a real treat.

Our chalet was on the beach, which sounds idyllic until the high tide relentlessly pounds against the wall at 3am. The noise is unbelievable. Forget about the soothing lull of water, this is like trying to sleep through Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture.

The food is fresh and plentiful in the hotels and resorts, since the land is so lush and fertile. We dined on seafood and chicken, vegetables we didn’t always recognize, and bananas served in a dozen different ways.

On the final day a battered taxi arrived to drive us to the airport. We checked in for our flight to the capital, Antananarivo, then walked back out again to have a drink in the nearby café. Even airport security is laid back here.

My connecting flight home was at 6am the next day, so we spent a night in a lovely hotel in a miniature forest just 20 minutes from the airport. I slept soundly, but I was wide awake long before the 4am wake-up call. Those pesky mosquitoes had struck again.