The most overused words in travel-speak must be ‘once in a lifetime.’

But if you’re open to a journey that has a habit of changing lives, I think I may have found it. It’s a trip on the Europa, a glorious sailing ship with riggings, a crow’s nest, a poop and sloop deck and other fascinating terms that baffle the average landlubber.

The Europa is largely crewed by people who signed up as paying passengers and forgot to ever disembark.

Now they sail from South Africa to Mauritius and on to Australia. Around the Cape Horn and up for a jol in Buenos Aires, before catching the Atlantic trade winds to sweep them up to Amsterdam.

Young and weather-beaten Chief Officer Ruud Blokzyl paints a bewitching picture of freedom and magnificent adventures. He talks of camaraderie on the cold night watch, of teamwork when the seas get rough and a spiritual awakening as you sail through the stark white nothingness of Antarctica.

“It’s not a life where you will become rich but you will be happy. It’s got fulfillment,” Blokzyl says. “As soon as you get the sailing virus you start becoming untenable in real life.”

I caught up with the Europa in Mauritius, as she sailed into Port Louis with two other Dutch Tall Ships, the ‘Tecla’ and ‘Oosterschelde’ to celebrate the 415th anniversary of the Dutch fleet landing in Mauritius.

Watching them sail into port was an exhilarating sight, kindling a desire for adventure and exploration that has hooked generations of sailors.

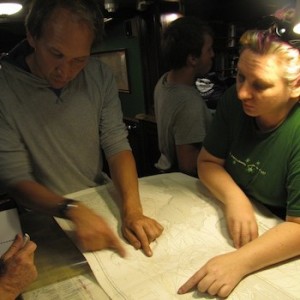

Later as we pore over maps in the gently swaying lounge I’m so entranced that I almost sign up and sail away. For about €100 per night you get three meals a day, the chance to learn new skills and make new friends, and plenty of time to explore the cities and ports en route.

Then I see the tiny cabins, and realise that living in close proximity to total strangers for several weeks may have its downside.

It’s that intensity of the experience that keeps people coming back, says Juanita McGarrigle, a pink haired Irish-Canadian. “If you want to go from destination A to B then fly, but if you want to experience going from A to B then take this ship,” she says. “It really is a life-changing experience for so many people.”

It was for her, as she came aboard as a paying passenger eight years ago and loved it so much that she returned as a volunteer. Now she’s like a water-borne flight attendant, training passengers to handle the various tasks that keep the ship heading in the right direction.

“It doesn’t matter what race or language or age you are, you’re all working together whether it’s to sail the ship or to peel the potatoes for dinner, and that’s what this ship is about. You leave technology behind and share your dreams and experiences and inspirations. You really get to know people on a different level and make intensive connections,” she says.

The ship suddenly lurches as I’m climbing a narrow ladder, and it reminds me that being on a tiny vessel in stormy seas must get a little scary. There are always two people on the deck on lookout duty, and when the weather is really rough they are literally tied to the instruments. Safely equipment is abundant too. “We have more lifeboats than we actually need. Titanic – lesson learned,” McGarrigle says. “We often stay inside and watch movies in bad weather, films like The Perfect Storm,” she jokes.

Sometimes the ship is swallowed by the sea, but as long as everything is tied down properly it always pops back up again, Blokzyl says. “The amount of wind a ship can take is almost endless before the construction breaks. We have much better information now than they did in the early 20th century and an engine so we can take evasive action. But the good thing about extreme weather is that it moves pretty soon. Maybe you have two days of hell but then it’s better.”

The Europa was built in 1911 and was rediscovered many years later abandoned in a Dutch shipyard. It was refitted with a generator and engine and modern navigational equipment, but the crew still uses traditional charts.

A permanent crew of about 14 is led by Captain Harko Lambarts, who started as a paying passenger himself. Each voyage can take up to 45 passengers, and on the most recent journey, 20 different nationalities were represented.

Those who adore the experience can return as volunteers, and it they survive on board for three months they start to earn a salary.

But being selected is not only about having sturdy sea legs and knowing how to splice the mainsail. “You have to have a personality that fits in because you’re living in close quarters for a long time,” McGarrigle says. “You need a good sense of humour and an excellent work ethic and a willingness to do what’s asked of you.”

Voyagers fall into three main categories. Some are fascinated by the history and art of sailing ships and want to know how everything works. Some are at a stage in life where they yearn to try something different or complete a bucket list. Most are simply adventurers, relishing the experience without needing to learn all the technicalities.

I watch as some of the passengers walk down the gangplank and head off to explore Port Louis. Everyone is laughing in a different accent as they wobble unsteadily, adapting to the unusual sensation of the ground beneath them holding firm.

It’s tempting to stow away among them. But if I sailed away, maybe I’d forget to ever disembark.

WHY DO IT:

For the love of adventure, the thrill of the open seas, the romantic notion of a travelling by sail. To learn bizarre new skills, make new friends and see odd ports you’ll never visit otherwise. To escape real life and – just maybe – decide you’re never coming back.

HOW TO SAIL AWAY:

The Europa sails year-round, with voyages varying for 12 to 111 days. Prices include all meals and a bunk in a shared cabin. Passengers are responsible for getting to and from the relevant ports. For more details and booking see www.barkeuropa.com or www.dutchtallships.com.