The sun was still asleep behind some distant peaks when I clomped out of the tiny town heading for the mountains. Soon it would be a blazing 35 degrees Celsius, and I didn’t want to be halfway up a mountain in that heat. Halfway down a mountain would be fine — but we were still on the upward trajectory.

The cunning plan was to complete the ascent in the shade, then take the sun-baked downhill at a leisurely pace. I jiggled my rucksack into a slightly less bothersome position, thought of how professional I looked in my hiking boots, and admired the gorgeous scenery of Andalucía in Southern Spain as it unfolded around me. Olive groves ran down the slopes, goats occasionally bleated and butterflies played in the grass. Last night, I’d slept in a quaint hotel in Cazorla, a small town we’d reached on a bus that swept ’round endless bends with a lake to the right and a lonely farmhouse to the left. Ancient Cazorla rarely sees any English-speaking tourists, since it’s well off the beaten track and the only real attraction is the hiking trail back out again. We’d enjoyed a lovely dinner just off the main square the night before, tucking into a three-course meal for a set price that makes eating out affordable and extremely filling. One course for €10 or a full three courses for €12 is hardly a difficult decision. And the cheesecake had been so exquisite that I’d kept eating long after filling up on both paella and lamb stew.

Now I was walking it off again, with frequent stops to admire the view, have a slug of water, slap on more suntan lotion, fiddle with my laces or take a photo. We weren’t the most gung-ho hikers, perhaps, but we did have a good laugh and debate some pressing social problems as we pottered along the peaks.

In one valley lay a crumbling monastery once inhabited by 30 monks. Now only one old Padre keeps the place alive, hiking to the monastery every day from the village several kilometres below. He wasn’t there when we arrived, and the gate to the garden was locked. Then we spotted a figure striding down the path behind us. The ancient Padre, storming along with his long brown robe flaring out behind him. We followed him ’round to a church at the back, where he posed, beaming, for photos. The monastery has no water or electricity, so when this final survivor of his band of Franciscan brothers meets his maker, the buildings will gradually decline into another of the desolate ruins that litter Andalucía.

Several hours later we stomped wearily into a village that seemed as deserted as the crumbling monastery. It was siesta time, and we found the entire population clustered into the bar watching a bullfight on TV. Sipping my drink, I felt terribly noble about my strenuous activity, until I figured out we’d set a cracking pace of 1km every 37 minutes.

Exploring cities is more my forte, and Andalucía is the perfect place to do that. Seville, Cordoba, Granada: even the names sound enticingly romantic. Seville is absolutely gorgeous. I was hooked from the moment the airport bus ferried me to the central train station, where I caught a bus across the road that dropped me off right outside my hotel. In the city centre buses are superfluous as this is a compact, pedestrian-friendly place. If you really insist on being driven around, try the horse-drawn carriages.

Seville’s centrepiece is the largest Gothic cathedral in the world, with a Guinness Book of Records certificate on display to prove it. Just around the corner is the Alcazar, a rambling Moorish palace with gorgeous gardens to get lost in.

Across the river, you’ll find San Jorge Castle, a fort where the Spanish Inquisition terrorized for 300 brutal years. The castle has been turned into a museum that’s surprisingly tasteful, rather than a graphic presentation of the horrors that befell anyone suspected of heresy. As I walked through the cells, I heard how prisoners weren’t told what specific act of “heresy” they were accused of. Some were simply tortured for being non-conformist, rich(er) or for owning land the inquisitor coveted, as it festered into malicious greed and corruption. Those who succumbed and confessed were killed, and those who didn’t confess were killed for being so stubborn. In one day in Seville alone, more than 300 people were burned at the stake.

As you leave the museum you emerge in a lively fresh produce market, where I bought a massive caracol — a Danish pastry the shape of a snail. Munching thoughtfully, I strolled along the riverbank, crossed another bridge, and caught a boat along the Guadalquivir River. There’s not a massive amount to see from the water, so I kept my eyes on a jogger, who gradually overtook us and disappeared into the distance. While most of Spain knocks off for the afternoon, there are always a few eccentrics doing their own thing.

It’s the evenings when Andalucian towns really come into their own. The first night I emerged from my hotel at 8 p.m., only to duck back in to put my shorts and T-shirt on again. Heat still enveloped me, and a lively summer vibe pulsed in the streets. Tapas bars were beginning to fill up, but much of the action only starts at around 10 p.m. when it’s cool enough to feel hungry. Couples and families are still eating in the pavement cafes long after midnight.

Seville’s architecture is achingly glorious. The centre feels modern yet ancient, with the buildings well preserved despite chain stores and boutiques taking over the lower floors. The university is housed in a massive building that was once the cigarette factory supposedly frequented by Carmen, the sexy senora of Bizet’s opera. Across the road are Maria Louisa Park and the ludicrously ornate Plaza d’Espana, built for the Ibero-American Exposition of 1929.

The archaeology museum is in the park too, but like many Spanish museums, you’ll be welcomed in English even though none of the exhibits have English explanations.

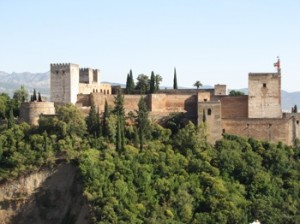

Andalucía has been fought over by the Romans, Visigoths, Vandals, Moors and Christians, and everybody left their mark. Often a church and a mosque are combined in one as Christians showed Muslims the door in centuries of skirmishes. The most elaborate example of one religion overthrowing another is in Cordoba, where the Arab Mezquita (mosque) dating from 719 AD was adapted by the Christians after 1236. At least they didn’t demolish it and start again, and queues now form to admire the bizarrely harmonious architecture that blends Moor and Christian under one roof.

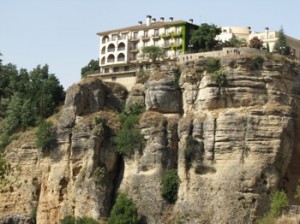

The amazing town of Ronda is another architectural achievement, perched on two sides of a crevice. Houses are literally built right on the cliff edges, making for spectacular views but probably excruciatingly high insurance premiums. I photographed Ronda from every possible angle, then disappeared down confusing side streets that wound and twisted and mysteriously brought me back out behind where I’d begun.

The sun was still scorching Seville when I returned, a fortnight after I’d first left. Since then I’d hiked, descended into a cave, had an Arab bath, eaten and drunk to excess, caught trains and buses and explored tiny whitewashed villages that closed entirely for an afternoon nap.

I’d wondered if I could live this way: abandoning real life to run a tourist office, perhaps, in a town that rarely sees any tourists. Going to work at 9 a.m., taking a five-hour siesta, then starting again once it cools down after 7 p.m.

Southern Spain isn’t just a collection of towns, cities and olive groves: it’s a way of life. It’s about gossiping at the supermarket checkout instead of serving the next customer. It’s chatting to strangers at the bus stop or on a park bench to say: “Hello, how are you? Hot today, eh?” It’s eating ice creams so rich that you can’t manage lunch afterwards. It’s about the shortest skirts you’ve ever seen, and playing dominoes in the bar. It’s the attitude that makes Spain the only country I know where even the hotels close for summer so the owners can go on holiday.