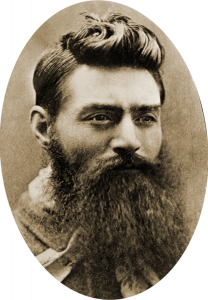

The photograph at left, taken by police photographer Charles Nettleton, shows the Australian outlaw Ned Kelly, on November 10, 1880 in Melbourne Gaol.

Less than twenty-four hours later, at 10:00AM on the morning of November 11, 1880, Kelly felt the hangman’s noose tighten around his neck just before he was hung following his conviction for murder. And so, at the age of 25, ended the short but eventful life of Australia’s most famous bushranger, Edward ‘Ned’ Kelly.

In Australia, Kelly’s story has taken on mythic proportions which readers outside the country may find hard to understand, and yet other countries have their own equivalents of Ned Kelly. The English for instance have Robin Hood, while in America, the outlaw Charles ‘Pretty Boy’ Floyd could also be compared to Kelly.

Edward Kelly was born in Victoria to an Irish convict father in June 1855. Considered by some to be a cold-blooded killer, to others he was a folk hero and symbol of Irish-Australian resistance to the British ruling class for his defiance of Australia’s colonial authorities. Following an incident at his home in 1878, Ned took to the bush with his brother Dan and two friends, Joe Byrne and Steve Hart. In the ensuing police manhunt, three policemen died at a remote bush location called Stringybark Creek. When Ned took the blame for all three deaths, the colony of Victoria proclaimed Kelly and his gang wanted outlaws.

The Kelly Gang, as they came to be known, eluded police for a further sixteen months before a final violent confrontation with police took place in Glenrowan, a small Victorian country town on 28 June, 1880. It was during this final shootout that the Kelly legend was hammered out in cold steel when Kelly – with guns blazing – appeared before the police dressed in his home-made plate metal armour and helmet.

Because the events surrounding the whole Kelly Gang era only occurred some 130 years ago, most of the small country towns that featured in his brief criminal career have remained remarkably unchanged across the intervening years. In fact, many of the buildings where Kelly and his gang carried out their raids, hold-ups and kidnappings still stand today, giving ‘true crime’ fans a chance to revisit the sites of his most famous exploits.

Here are six ‘must see’ locations for anyone interested in exploring the Kelly legend further. While not in chronological order, in terms of the events that marked the Kelly Gang’s career, the route mapped out here (totalling approx 570 km) will take at least a couple of days to cover properly, so take it easy and allow plenty of time to see the major buildings and sites listed below.

A. Old Melbourne Gaol

Starting at the end of the Kelly story, a visit to Old Melbourne Gaol is a must. It is here that Ned Kelly spent the last few weeks of his life, and it is here that you can see his death mask, revolver and a replica of his suit of armour. You can also visit his cell, the gallows (where 134 other prisoners were hung), and other locations in this historic landmark.

B. Euroa

Following the killings at Stringybark Creek (see below), the gang committed two major robberies, at Euroa, Victoria and at Jerilderie, New South Wales. Although now privately owned, the former National Bank building in Euroa, which the gang raided on 10 December 1878, still stands on the corner of Binney Street and Railway Street. In fact, the area around Binney and Railway Streets forms the commercial centre of Euroa and a walk around this area reveals a number of historical buildings including the post office, the former National Bank building, the Euroa Hotel, and Blairgowrie House.

Adjacent to the park in Kirkland Avenue is the old Farmers Arms Hotel (built in 1876) which now houses the Farmers Arms Museum with its collection of local memorabilia.

C. Benalla

Benalla is another of the towns that feature prominently in the legend of Ned Kelly. It was in Benalla, in 1869, that the 14 year old Ned Kelly was charged in the Benalla Courthouse (at 69 Arundel St.), with assaulting and robbing a Chinese immigrant, a crime for which he was found not guilty. Kelly again appeared at Benalla courthouse in 1877, charged with being drunk and disorderly and riding a horse on the footpath. The Commercial Hotel (which still survives), became the headquarters for the ‘Kelly hunt’ in 1878, and in 1880, Ned was held at Benalla police station en route to his hearing at Beechworth after the siege at Glenrowan.

The Benalla Costume and Pioneer Museum, at 14 Mair Street, houses the previously mentioned green (and now blood stained) sash Kelly was wearing beneath his armour during the siege at Glenrowan. Along with the sash, the museum’s permanent Kelly Story exhibit also includes his horse bridle, letters, documents, and other memorabilia.

Following the final siege and shootout at Glenrowan (see below), the body of gang member Joe Byrne was taken to Benalla and strung up as a curiosity for photographers and spectators alike. Since his body was not claimed by his family, he was buried by police in an unmarked grave in Benalla Cemetery (on Baddaginnie Road). The site has since been identified by local historians and is now marked by a modest gravestone.

D. Glenrowan

Glenrowan is the site of the Kelly Gang’s ‘last stand’ which took place in and around the Glenrowan Hotel. The hotel was burned to the ground during the siege, and today, nothing substantial remains of the original building. One of the jails in which Kelly was incarcerated has become the Ned Kelly Museum, and weapons and artefacts used by Ned and his gang are exhibited there. A thriving tourist trade dealing in the usual tourist kitsch (tea towels, key rings, ‘Wanted’ posters, figurines, and other such trinkets), has grown up around Glenrowan’s status as the site of Ned Kelly’s capture, but I found that this cheap commercialisation made the town the least interesting of all the sites on this route.

E. Beechworth

Where Glenrowan tends to disappoint the serious researcher into the Kelly legend, Beechworth more than makes up for any sense of disenchantment. There is so much to see here that one could easily spend a full day in the town. Recommended activities include the daily 60 minute Ned Kelly Walking Tour, which takes in all the main locations that feature in the Kelly story. These include the Beechworth Courthouse (built 1858) where Ned and various members of his family appeared on numerous occasions; and Beechworth Gaol (built 1855) where you can see Ned Kelly’s cell and other items.

F. Jerilderie

Following the killings at Stringybark Creek, the gang eventually made their way to Jerilderie, New South Wales where they embarked on a crime spree that involved hostage taking and robbery.

It is worth noting that after Beechworth, Jerilderie has the most Kelly-related buildings and sites. Here you will find numerous heritage sites including the Post and Telegraph Office, Blacksmith’s Shop, Jerilderie Courthouse, and the Royal Mail Hotel, where Dan Kelly and Steve Hart kept hostages entertained (and happy) by plying them with free drinks. Meanwhile, Ned Kelly and Joe Byrne were busy robbing the local bank of £2,414, where Ned also burned all the mortgage deeds held in the bank.

Ned Kelly in Australian Iconography

Although Ned Kelly was captured, and the three other gang members died as a result of the shoot-out – and despite Kelly’s eventual execution – his daring and notoriety turned him into an iconic figure in Australian history, as evidenced by the mass of folklore, literature, art and film that has been devoted to the man and his activities.

Kelly appears across a range of Australian iconography that includes the artist Sidney Nolan’s famous series of Ned Kelly paintings. Countless books have been written about Ned Kelly and at least ten movies (including the 1906 film, The Story of the Kelly Gang, now recognised as the world’s first feature-length film) have tried to tell his story. Ned Kelly, starring Rolling Stone Mick Jagger opened to much controversy in 1970, while the most recent 2003 retelling of the Kelly legend – also called Ned Kelly – starred the late Heath Ledger.

Following his execution Kelly’s body was dissected, with his head and organs removed for study, while his remains may or may not have been buried in Melbourne Gaol’s mass graveyard. Kelly’s head was given to phrenologists for study before being returned to the police, who for a time used it as a paperweight. At some unknown date, the skull was given to the Institute of Anatomy in Canberra who, in 1971, gave it to the National Trust. It was displayed at the Old Melbourne Gaol from where it was stolen in December 1978.

For more than 30 years, a Western Australian farmer claimed to have the skull in his possession. In 2009, the farmer finally gave the skull to government authorities who had it forensically examined by a team of scientists at the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine. After a year of subjecting the skull to the latest scientific techniques and intense historic research, the scientists announced that the skull was not Edward Kelly’s.

To this day, despite continuing speculation, Ned Kelly’s skull remains lost – or at least hidden from public view. All this and more only shows that the legend of Ned Kelly is not about to die out anytime soon.