There isn’t a single wisp of smoke curling out of the top of Mount Vesuvius as we walk up its stony brown slopes.

There isn’t a single wisp of smoke curling out of the top of Mount Vesuvius as we walk up its stony brown slopes.

A few birds are twittering in the bushes, but we leave we them behind as the path rises above fertile ground. It’s silent, except for the scrunch of feet on clinker. It’s too quiet, too calm. Are we about to get taken out in an unexpected rumble of smoke, ash, flames and lava spewing into the skies and tumbling down upon us?

Ok, so I have an over-active imagination. But after being awed by the excavated city of Pompeii, you realise how lives can be completely obliterated in moments. And Vesuvius is overdue for an eruption, says Guido, our volcanic escort.

We reach the summit of Italy’s most famous furnace and look into a crater of dull grey, brown and orange-tinged rocks. There’s almost a sense of disappointment, as you half hope to see a menacing lake of bubbling lava. There’s just a barren hole, with a few tufts of grass beginning to gain a foothold. But now we can see trails of smoke drifting from cracks in the walls. Looking all wispy and innocent, despite being the smoking guns that confirm the raw, untamed power below.

Volcanoes have been back in the news in a big way since Iceland’s unpronounceable Eyjafjallajokul erupted and closed European airspace last year. That was probably the first time 10 million people who were left stranded have ever been affected by a volcano, and as volcanic impacts go, it was a mercifully minor affair. Then Guatemala’s Payaca and Ecuador’s Tungurahua volcanoes blew their tops, as Mother Nature enjoyed a fiery revival.

Guido settles on the edge of the crater and explains the sophisticated monitoring devices that trace every burp, hiccup and sigh Vesuvius makes. They should be able to pinpoint exactly when it’s going to blow. Then he shrugs and admits the evacuation plan is a nightmare. The slopes are home to half a million people, and that’s without factoring in nearby Naples, crammed with at least a million people who are probably too stubborn to bale out anyway. Since the roads around Naples are already a traffic disaster, trying to evacuate by road would create gridlock.

We stroll down the slopes again, fingering fragments of rock and trying to imagine this benign mini-mountain hurling out death and destruction.

I can’t visualise it as I stroll around Pompeii either, following wide, almost perfectly preserved Roman streets, and walking into an amphitheatre with room for 20,000 spectators. I admire the remains of astonishingly grandiose temples, and look at urns and bowls stacked neatly in the bakery.

I can’t visualise it as I stroll around Pompeii either, following wide, almost perfectly preserved Roman streets, and walking into an amphitheatre with room for 20,000 spectators. I admire the remains of astonishingly grandiose temples, and look at urns and bowls stacked neatly in the bakery.

The Villa dei Misteri at the far end of the city is the closest to Vesuvius, with amazing colourful frescoes in the room where an upper class Roman family dined. I know that if I’d been there on August 24, 79AD I’d have gawped in fascination as Vesuvius started its spectacular pyrotechnics. I’d never have dreamt the fizzing flames could unleash the deadly concoction of ash and melting rocks that covered Pompeii and sealed in all it inhabitants.

I wonder whether anyone had time to evacuate. One display board answers that, telling us “a sudden tremor abruptly interrupted the daily routine of the inhabitants of Pompeii. That was followed by a tremendous blast signalling the beginning of a violent eruption with a column of lapilli rising over 20,000 metres into the sky. This hailed down upon Pompeii, submerging the city in a few hours in three metres of material.”

Then hot gas and burning ash swept through, clogging the lungs and causing death by suffocation. After successive waves of destruction, Pompeii was lost entirely under six metres of debris.

In one room a body sits with its knees drawn up and futile hands trying to protect its face. Another is lying flat, dead in bed, perhaps. They’re plaster casts, made by pouring plaster into the space created when a body decays within the rock encasing it. I can’t help staring, because it’s the bodies that make you comprehend. Plaster casts that say “this is where I died” rather than pillars that say “this is where somebody once built.”

Yet the most popular sight in Pompeii isn’t the bodies, or the beautifully preserved public baths. It’s the brothel, and if the crowds queuing to get in today reflect the queues of the Roman era, the poor girls must have been worked off their feet.

It’s a tiny building, and reminds you how small those Roman men were. In height, I mean. The bedrooms leading off the corridor are ridiculously tiny, and above each room is a fresco showing the occupant’s speciality. Pompeii was a seaport, so foreign sailors could just point at what they wanted rather than learn a whole new lusty lexicon. It’s hard to see who is doing what to who, with the erosion of time. But you queue because everyone wants to figure out the faded drawings.

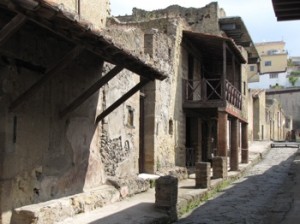

The small seaside resort of Herculaneum was also obliterated by Vesuvius, in an unstoppable stream of molten lava. Herculaneum is nowhere near the sea now, because the lava literally created a solid new landmass. It’s marvellously well preserved, but lacks Pompeii’s ability to conjure up a sense of how life must have felt in those heady Roman days.

Perhaps comparing Pompeii and Herculaneum is like comparing seething Naples with sleepy Bomerano, a mountain village behind the stunning Amalfi coast. Bomerano’s beauty is that it’s a handy and relatively cheap base from which to explore Vesuvius, Pompeii, Naples and the gravity-defying cliff-face towns Amalfi and Positano.

Positano is pretty but far too full of tourists. Give me Naples any day, with its big city life and grime, lively markets, sophisticated shopping malls and splendidly ornate buildings.

Positano is pretty but far too full of tourists. Give me Naples any day, with its big city life and grime, lively markets, sophisticated shopping malls and splendidly ornate buildings.

The Neapolitans take a maverick pleasure in living in the shadow of danger cast by Vesuvius, proudly describing themselves as hot, passionate and volatile like their land. Naples is notorious for being Italy’s most seedy, edgy and disreputable city, but I don’t pick up the slightest sense of that even in its narrow backstreets. In fact I feel tempted to mug someone myself, just to help Naples uphold its possibly undeserved reputation.

In a street market I’m fingering the leather belts, needing a new one after days of delicious three course dinners. A hunky stranger materialises by my side, saying it’s dangerous to buy things on the streets because the bad boys of Naples will take advantage of me. It sounds delightful. “Aren’t you a Naples bad boy?” I ask, and his only reply is to lift an eyebrow over a suggestive, sexy smile. Yep, those Neapolitans can smoulder in a way that puts even Vesuvius to shame.